One of my students a beginner (casting rather well) recently had an outing casting from a boat. There was the eternal wind blowing and the boat moving and all that. But the main issue was that the leader was misbehaving and didn’t turn over. The caster was struggling to lay out the line and the leader straight. The caster had no control over the leader and fly, and never was able to lay the ensemble out straight

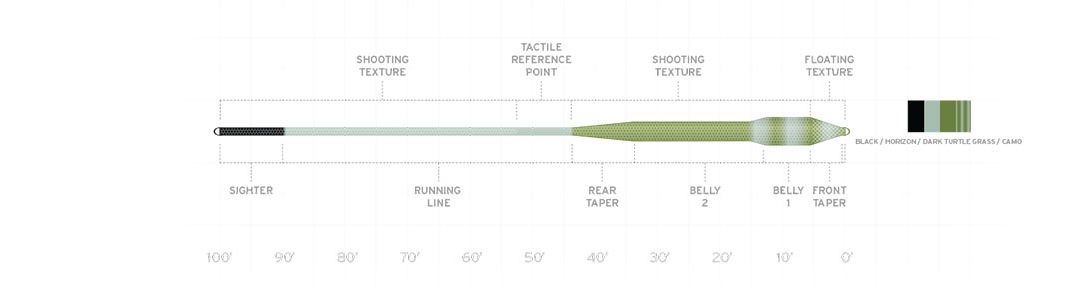

We all have been there at some point in our journey. Now, I did some sleuthing of the equipment. The rod, an old stalwart #9 Sage II was not the issue. The #9 fly line was a new correctly sized one – not the problem. Now, the leader turned out to be a 12‘long hand-tied affair with a butt section of 0.024‘‘. The fly used was a weighted (bead chain) streamer.

Length of leader

Long leaders (10’ or more) are frequently advocated by guides and experienced anglers. Yet, as the leader lengthens it gets to be much more difficult to cast. The savants forget those beginners will struggle with long leaders plus the wind and a heavy fly. The leader must work for the angler using it, and it makes no sense to use a long leader if it does not turn over. You are better off with a shorter leader that you can turn over and lay out straight. Even if a long leader is preferable, if the caster can’t make it work, it isn’t the right leader.

Butt thickness

My #9 bonefish fly line has a 0.040’’ tip diameter (have micrometer will measure). That diameter calls for the butt’s leader to be around 70% of the fly line’s diameter. 0.040 x 0.7 = 0.028’’ for the two to have comparable masses. Our leader’s butt was not terrible (0.024’’) but not optimal either. For optimal transfer of energy from the fly line to the leader, the masses of each at their juncture must be close to the same. And the longer the leader the more important it becomes that the butt is heavy enough.

https://everyjonahhasawhale.com/blog/your-butt-is-too-small/

Heavy fly

We all know that heavy flies can kick when we cast them. Heavy flies are usually on the big side too and will have more drag. So, using a smaller lighter fly, if possible, will help.

https://everyjonahhasawhale.com/blog/the-fly-line-kick/

https://everyjonahhasawhale.com/blog/casting-a-heavy-fly/

The caster’s ability

The idiot savants of casting can fling out just about anything – long leaders with big flies no problem. However, beginners can’t do that. We must always curtail our advice to the ability of the caster being advised.

My advice for beginners

Buy ready-made leaders and forget the advice of the experts they can tie their own leaders, but it takes experience to get there. Ready-made leaders are now high quality and thus you will have fewer knots (it takes experience to tie great knots). Pay attention to the butt thickness. Quality leaders will have the butt diameter printed on the info sheet. A very good bet is that anglers’ butts are too thin. If you can’t turn over your leader – it is too long and/or fly too heavy/big for your casting abilities. You are in the game with a 9’ leader and your preferred fly laid out straight – but not if you have a 12’ leader collapsed in a bird’s nest.

Your casting abilities at any time are what they are i.e., not a variable, but leader length, butt diameter, and fly can be varied to get the desired outcome. There is no need for self-inflicted wounds or unforced errors. It is difficult enough as it is.

https://everyjonahhasawhale.com/blog/take-me-to-your-leader-from-butt-to-fly-through-the-tippet/

https://everyjonahhasawhale.com/blog/ready-made-leaders/

Technical consultant: Bruce Richards

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Sigurbrandur Dagbjartsson

Sigurbrandur Dagbjartsson

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Jónas Magnússon

Jónas Magnússon Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson

Jonas Magnusson